CS Insights: Why The Media Loves Covering Private Credit

When I started in late 2007, financial journalism wasn’t an obvious choice.

Lacking, say, the morbid glamor of war correspondence or the popular reach of sports writing, financial journalism provided a kind of informational annuity to an interested audience; markets moved up a bit or down a bit, the world outside carried on. Until it didn't.

The 2008 crisis elevated financial journalism to a general audience anxious to know what it meant (and how much it was costing them), then kept mesmerized by tales of lurid greed and unfolding national economies.

That urgency has receded, but financial journalism hasn't lost its taste for stories able to transcend the niche. Crypto, Meme-Stock Mania, Elon Musk, and the SPAC boom are recent examples. Going a little further back, corporate inversions had a mainstream moment. The resonant qualities of these stories, rapid growth, shaky ethics, fast characters, a sense that it might all blow up, etc., feel obvious in hindsight.

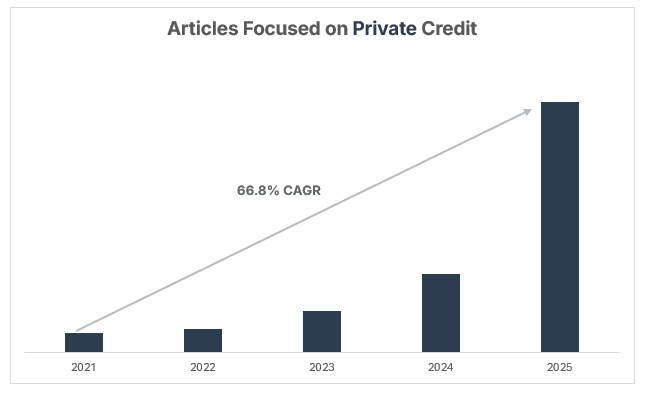

Financial media’s current obsession with private credit is harder to understand. Loans made to and traded between established institutions; private credit has grown rapidly in the last few years into an industry worth about several trillion dollars today. But it is hardly an exotic idea. The industry’s front men wear suits. Their product isn’t traded on the public markets but that’s true of many things that aren’t particularly interesting. It may blow up, but the evidence that it is about to is limited.

So, why the interest?

I have long been convinced that it is, at least partly, in the name. Despite there being lots of public data on private credit, there is a tendency to think of it as, well, private. Journalism isn’t set up to value the known, it thrives on illuminating that which is hidden from plain sight and is, thus, drawn to the opaque. That’s why rolling news is stuffed with independent clauses like Exclusive, Breaking, or Just In, regardless how interesting the story otherwise is. Revelation is value.

But rather than speculate, I asked those covering the story what makes it worth their time.

Liz Hoffman, Semafor's Business and Finance Editor

"It's new, it's big, and it might end badly. Plus, there's the (slightly manufactured) tension of banks losing ground to these upstarts, many of which were founded by breakaway bankers. In fact, banks have found a new spot in this ecosystem; each to their corner of this particular Rube Goldberg machine. The press also assumes the next crisis will look like the last one. The last crisis, in 2008, involved lenders getting out over their skis.

A lot of the pearl-clutching is overblown — it's not like banks have always been paragons of responsible lending, and private credit is a lot less prone to runs — but you can't have $2 trillion go into an untested new asset class this quickly without a few accidents. Reporters get paid to find those accidents.

Also, it's private, which sort of suggests it's secret. It's not — many of these funds disclose every loan they own every quarter — but reporters do love a secret."

Lauren Thomas, Wall Street Journal's Lead Deals Reporter

"It seems almost every story is a private credit story nowadays. It's such an interesting string to pull on for the media because there is so much uncharted territory and the general lack of transparency in the system lends itself to journalists unraveling the next big story. A string of recent bankruptcies (i.e. First Brands) involving private credit financing has added more fuel to this fire. The fact that some of the biggest names on Wall Street still disagree on this topic makes it all the more enticing to follow along."

Sujeet Indap, Financial Times' Wall Street Editor

"Private credit is the natural conclusion of the 2008 financial crisis with capital intermediation migrating from the traditional, highly regulated banking sector to the looser asset management sector. As it happens, the biggest players in private credit are legacy private equity firms with their reputation for greed and treachery, now trying to refashion themselves as sober and dull lenders. Anything that is nascent and not well-understood yet is going to make for a good story, especially when erstwhile private equity bad boys are the main characters."

.png)